1 Rebooting Your Future

The first part of this book is about designing your future. Before we get started, we need to reboot and tackle a fundamental design issue. Why the hell would you want to bother reading this guidebook when you have so many other things to do right now?

- ✅ You are a busy person, YES!

- ✅ Your time is a precious and finite resource, YES!

- ✅ You could be spending that precious time in lots of other ways right now, YES!

- ✅ There are mountains of self-help guides and courses already, YES! YES!

- ✅ Do you really need yet another guidebook? YES! YES! YES!

You should read this guidebook because it is different to all the other guidebooks! It will help you design, test, build, debug and code your future in computing.

Before you start either designing or coding, we need to reboot. So come with me down the proverbial rabbit hole in figure 1.1 and let me explain… 🐇

Figure 1.1: Shall we go down the rabbit hole? Rabbit Hole learning by Visual Thinkery is licensed under CC-BY-ND

Your future is bright, your future needs rebooting, so let’s reboot your future.

1.1 What You Will Learn

After reading this chapter you will be able to reboot your future by :

- Setting your expectations for using this guidebook, and opening some doors to your future

- Travelling down the rabbit hole into the underworld of employment

- Discussing some of the gaps that exist between formal education and employment and how you can bridge them

1.2 Let’s Go Down the Rabbit Hole

In the novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (L. Carroll 1865), the protagonist Alice follows a white rabbit down a hole. What she discovers is a strange underground world populated by weird and wonderful characters. The world of work can sometimes be a mysterious underworld where you adventure in wonderland accompanied by colourful characters.

You will spend lots of time in this wonderland, potentially as much as 80,000 hours as part of the ~4,000 weeks of your life. (K. Byte 2020; Burkeman 2021) So join me down the rabbit hole, it’s fun (honest), and sooner or later you’ll have to come down here anyway. So open up the door to the new possibilities in your future.

1.3 Opening Your Future

Studying at University opens new doors to your future, some of which will take you down rabbit holes. As the poet Lemn Sissay puts it (figure 1.2):

Figure 1.2: Open all doors, open all senses, open all defences, ask: What were these closed for? From Inspire and be Inspired by Lemn Sissay whose poetry is even better when you hear it, rather than just read it youtu.be/WzZs1w3NWzg. (Sissay 2015) Portrait of Sissay speaking in 2010 by Philosophy Football via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/3VYT adapted using the Wikipedia app

So University is a fantastic opportunity for you to open lots of new doors in your life and see where they take you.

1.4 Maximising Your Future

As well as opening your future, studying at University is about investing in your future. You’re spending lots of your time and money at University. Hopefully, you’ve picked a subject that stimulates and challenges you intellectually while allowing you to find and develop your unique talents. But there’s another reason that you probably chose to study at University and that was to improve your job prospects. This guidebook will:

- Help you maximise the return on investment (ROI) of the substantial amount of your time and money you have already put into your education, from primary school through to University (H. Byte 2023a; J. Britton et al. 2020; E. Blair 2021)

- Give you an overview of important professional issues that are sometimes neglected or sidelined in school and University curricula

- Highlight and review essential resources beyond this guidebook that will help with the above

All of the resources that can help you are scattered around in lots of different places. There are books, there are videos, there are podcasts, there are websites, TikToks, YouTubers and jobs boards. There are online courses, blogs, social media, newspaper columns, journal articles, AI, marketing material and many other good resources. It is overwhelming.

1.5 Your Future is Your Responsibility

When Andy Stanford-Clark started working at IBM as a graduate fresh out of University, his manager gave him the career advice shown in figure 1.3:

Figure 1.3: There’s only one person who REALLY cares about your career, and that’s you. Quote via Andy Stanford-Clark (Stanford-Clark 2019) to an unattributed IBM manager. Image of Andy by Gizmo~enwiki via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/3TSn adapted using the Wikipedia app. Thank you Andy for permission to use your photo.

Andy is now Chief Technology Officer (CTO) of IBM in the UK and an IBM Master inventor, so it was probably good advice. There are plenty people who can help design and build your future, ultimately it is YOU who has to take responsibility for the implementation (if you like, the code). The sooner you get coding the better.

At University, there are lots of people can help design and build your future: peers, friends, academic staff, your careers service, employers and your wider social and professional networks but ultimately it is your responsibility to sort out whatever comes next. That might sound obvious but don’t wait to get started later or for somebody else to do it for you, because it probably won’t happen.

1.6 Your Degree is Not Enough

You have worked hard to get the grades you needed to get into University. You’ve spent (or are spending) a significant amount of time and money studying your chosen discipline. You are really geeking out by going deep into your subject for a substantial period of time. Geekery, by which I mean being interested in a subject for its own sake, is a good thing. Earning the title geek is a compliment, not an insult, and you should wear your geek badge with geek pride! Some people even say:

- The geeks will inherit the earth, see figure 1.4

- The (geeky) weirdness flows between us, anyone can tell to see us (Mascis 1988)

YOU are a geek, so where is your inheritance?

Figure 1.4: Blessed are the meek geeks, for they shall inherit the earth. (Evangelist 1611; Robbins 2012) You are a geek, so where is your inheritance? Image of stained glass window by Norbert Schnitzler via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/43LN adapted using the Wikipedia app

As a studious geek you might be tempted to believe that the world owes you something in return for all your geekiness. Unfortunately that’s not the case.

At some point during or after your study, you might find yourself applying for a graduate job or graduate scheme. EVERYONE applying for these opportunities will have a degree or be rapidly on their way to getting one. So having a degree, even a really geeky one isn’t going to set you apart much from your competition. Even having a good first class degree may not distinguish you that much your competitors (Coughlan 2019a; Borrett 2019). Some employers would rather not know (or don’t care) what University you went to, so your education might not make you stand out as much as you might like anyway. (Agnew 2016; Garner 2015)

What WILL distinguish you from your competitors is:

- your

experience: see chapter 5 - your

projects: see section 8.7.5 - your communication skills:

- your actions: what have you done with all of the above? How have you applied these fundamental communication skills to perform higher level communication tasks such as understanding, negotiating, persuading and leading etc. See examples of actions in chapter 10

- your

resultsandevidence: seeC.A.R.Ein section 8.7.8: context, action, results and evidence. We’re talking about all your results, not just exam results. - any

leadershipyou can demonstrate orawardsthat you have picked up along the way, see section 8.7.6

If you think that your degree will be enough to get you the job you want, bear in mind that:

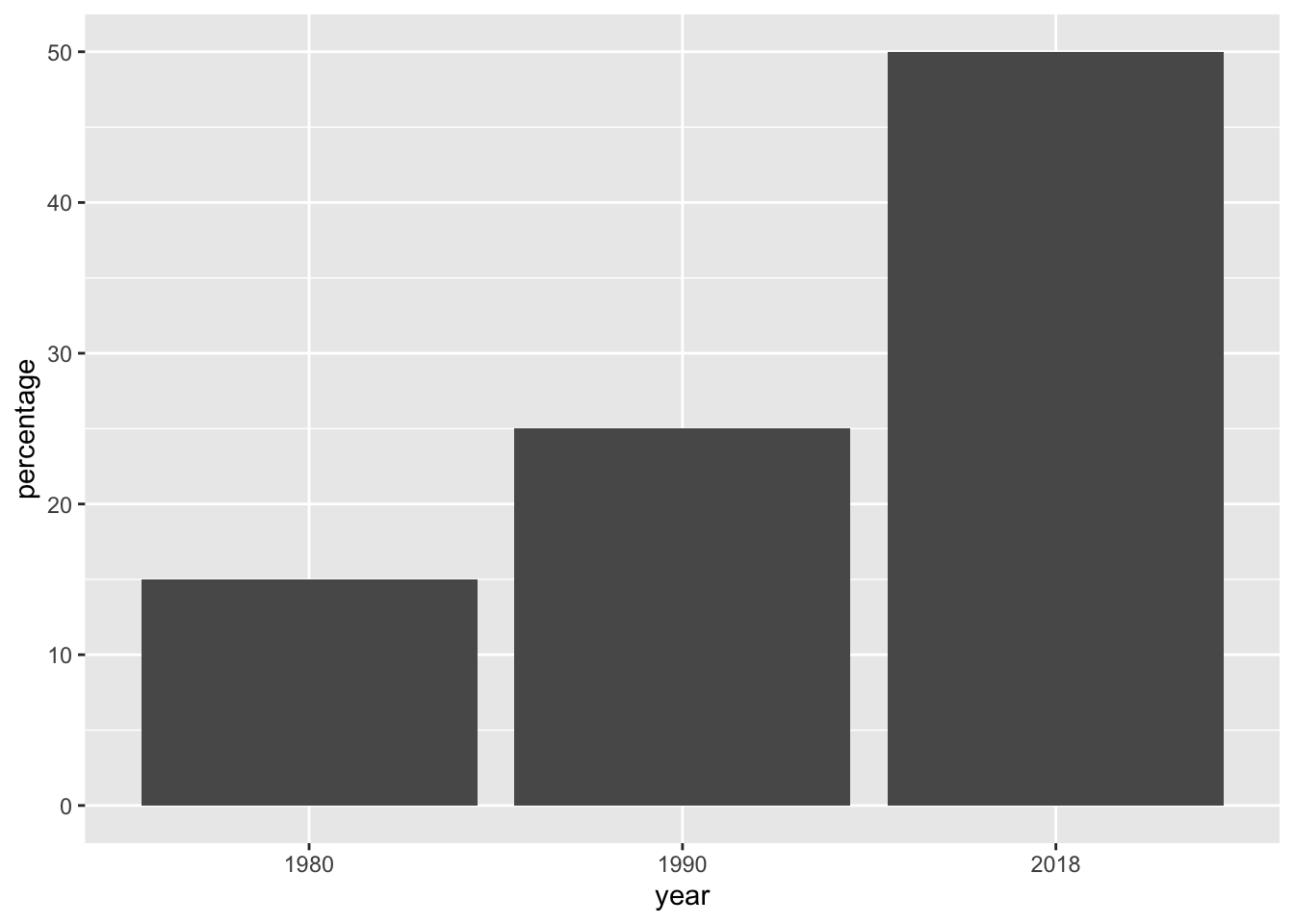

- There are more and more graduates, the UK for example recently passed the milestone of 50% of young people going into higher education. This compares to just 15% of over 18s who stayed in higher education in 1980 (Coughlan 2019b)

- While a degree is a necessary condition for joining a graduate scheme or taking a graduate job it is not a sufficient condition. Having a degree will not set you apart much from your competition, because every applicant will have a Bachelors degree (minimum).

- There are lots of graduates in your discipline. In the UK, for example, around 9,000 students graduate every year in Computer Science. If you’re studying in the UK, what makes you different from the other 8,999 computer scientists graduating in your year?

##

## Attaching package: 'dplyr'## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## filter, lag## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

Figure 1.5: Percentage of young people in the UK going into higher education between 1980 and 2018. Over the last forty years, the proportion of young people going into higher education has more than doubled from 15% in 1980 to over 50% in 2018. Data taken from BBC news article on the symbolic target of 50% at university reached (Coughlan 2019b)

As Sally Fincher puts it:

Computing is one of the largest subject areas in UK higher education, and is taught in almost every institution, graduating around 9,000 students every year

Now, don’t be disillusioned by the statistics because any degree can open doors to many careers in computing. Studying computing opens up plenty of doors, see figure 7.9. According to Charlie Ball, it is a myth that there aren’t enough graduate jobs; one of four myths in the UK about the graduate labour market:

- Myth 1: Everyone goes to university nowadays : ~50% isn’t everyone (Ball 2022)

- Myth 2: There aren’t enough graduate jobs, see figure 1.6 (Ball 2022)

- Myth 3: Some degrees have little value to employers, see chapter 7

- Myth 4: All the best graduate jobs are in London, (or your local big city) see chapter 12

Figure 1.6: Some people have argued that some countries have too many graduates. As of 2023, the UK has one million more professional jobs than workers with degrees, suggesting that the UK probably needs more, not fewer graduates. Image from an orginal tweet quoting a report by Universities UK. (Ball 2022)

What the data in figure 1.5 show is that you’ll need to look beyond your formal education to distinguish yourself from your competition. Your degree can certainly help you start a career, and computer geekery is a commercially valuable skill but a degree (however geeky) is typically not enough by itself.

There’s plenty of graduate jobs for you to apply for, but that doesn’t mean its going to be easy to walk into one when you graduate. Employers are looking for more from their employees than just having a degree, see chapter 5.

1.7 It’s Too Late When You Graduate!

You might be tempted to postpone making difficult career decisions:

- I’ll do it tomorrow …

- I’ll do it next week …

- I’ll do it next year …

- I’ll finish this assignment …

- I’ll finish this exam …

- I’ll finish this semester …

- I’ll finish my degree first, see figure 1.7 …

Procrastination is a part of the human condition and its not necessarily a bad thing. Software engineer Paul Graham and journalist Oliver Burkeman describe three types of procrastination:

- bad procrastination (Graham 2005a)

- good procrastination (Graham 2005a)

- better procrastination (Burkeman 2021)

We all procrastinate because there’s an infinite number of tasks we could be doing but a finite amount of time in which to do them, around four thousand weeks, depending on what you count. (Burkeman 2021)

Figure 1.7: Procrastination: the attitude of “I’ll get my degree out of the way first then worry about jobs and careers when I finish University” is bad procrastination. It’s too late when you graduate to start thinking about what might come next (Graham 2005a) Stressed procrastinator picture by MismibaTinasheMadando on Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/3TXo adapted using the Wikipedia app

Postponing decisions about your future is usually bad procrastination, because you risk neglecting the wrong things. You are relying on doing all your (career) testing at the end, when you graduate. You are procrastinating the testing stage of your career development, when its often better to test early and test often, so:

- ❌ “test-last (career) development” where you get experience at the end, after you graduate

- ✅ “test-driven (career) development” (TDD) where you get experience before you graduate

It probably doesn’t help that many of the issues described and discussed in this book are typically not closely integrated into the curriculum in Higher Education. You’ll often find them on the edges, or completely outside of, standard University curricula.

Despite being sidelined, these issues matter and it is in your own self interests to start thinking about them right now. According to recent estimates by Investors in People, the average person spends 80,000 hours working during their lifetime. (K. Byte 2020) So, whatever you end up doing after University, you’ll be spending a lot of time doing it. Difficult decisions often get sidelined but it is never too early to experiencing your future, see chapter 5.

If you want to work for a big name like those in section 5.3.3 or 11.3.2, many of the larger graduate employers expect you to have some experience (see chapter 5) before you graduate. A large chunk of vacancies on graduate schemes are filled with people who have already been employed as interns or placement students within that (or another) organisation. So the sooner you start investigating employers by getting some experience the better decisions you’ll be able to make about what comes next. It’s (usually) too late when you graduate.

That doesn’t mean you have to know EXACTLY what you want to do when you finish. Lots of students don’t and I certainly didn’t when I graduated. I’d done a gap year teaching in India, two summer internships (in Sweden and the United States) and a year-in-industry in the UK and I still graduated with no clue as to what I wanted to do next! The important thing is that you make a start by getting some experience, paid or otherwise, see chapter 5. Sometimes knowing what you don’t want to do is just as valuable as knowing what you DO want to do. Either way, your future starts now, see figure 1.8.

Figure 1.8: Your Future starts now, not at some point later in time like when you graduate. Whatever stage of your study you are at, there’s plenty you can do to start experiencing your future today, see chapter 5. Experience will make it easier to navigate your future. THE FUTURE IS NOW by Everydayphrase linktr.ee/everydayphrase

Computer scientists call this problem “search space reduction” (Ferrari, Marin-Jimenez, and Zisserman 2008). You have a feasible region of future possibilities and you need to narrow down the candidates. You could think of coding your future as an optimisation problem.

Start optimising now, by getting some experience because it’s too late when you graduate. 🎓

1.8 Yes, This WILL be on the Exam

Students love to ask their teachers “will this be on the exam”? The short answer is YES (and NO)! Yes, this will be on the exam, but NO the exam won’t be set by your University. Unlike other courses you’ve done, the examinations for this course aren’t set by your University but by employers. Roughly speaking, there are three kinds of examinations that you’ll need to get good at, shown in Table 1.1

| Examination | What examiners are assessing | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| CV, application form covering letter |

|

pass/fail |

| Interview |

|

pass/fail |

| Employee performance |

|

pass/fail |

So, yes, this will be on the exam, but no, the exams are obviously not set, administered, invigilated and marked by academics at your University. The exams are set by employers and the results are brutally binary:

- PASS: you’ve got the interview, job or promotion or…

- FAIL: none of the above. Next!

One of the challenging things about employers exams are, they typically do not have the bandwidth to give applicants useful feedback, other than a simple pass or fail. When it comes to job applications software engineer Gayle Laakmann McDowell calls this the “black hole”. The gravitational force of employers black holes is so strong that no CV or Résumé can escape, we’ll say more about this in chapter 8 on debugging your future.

Figure 1.9: So no this will not be on the exam set by University, but yes it will be on the exams set by employers. Some of the most important exams you sit at (and after) University are set by employers. This guidebook will help you prepare for those exams and increase your chances of passing them. Gimme some credit figure by Visual Thinkery is licensed under CC-BY-ND

It’s a similar story with interviews, if you botched an interview question or came across badly, it can be really difficult to find out from the employer what you did wrong. That makes it harder to learn from your mistakes.

1.9 Practicing Your Future

There are practical exercises, for you to get your hands dirty with. Each chapter incorporates activities including individual exercises, group exercises, quizzes and points for wider discussion. You’ll get a lot more out of this guidebook by doing the activities, rather than just reading it.

1.11 Crediting Your Future

Get credit for your contributions. As well as being openly accessible on the web, this book is open source too. What this means is, you can contribute in several ways described in section 0.8. All the written content for this guidebook is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND, see the license in section 0.12.1.

1.12 Your Future is Different

I’m writing this guidebook because I think students like you need resources to help you design, build, test and code your future in computing. I’m offering information, advice and guidance to help you learn to compete for jobs while at University, or shortly after graduating, in a flexible way.

I’ve searched high and low but can’t find anything suitable that meets all the requirements of the students I teach. Some problems with the resources that are already out there, and how this book addresses them, are shown in table 1.2.

| OTHER guidebooks | THIS guidebook |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To following sections give a bit more detail on the differences outlined in table 1.2.

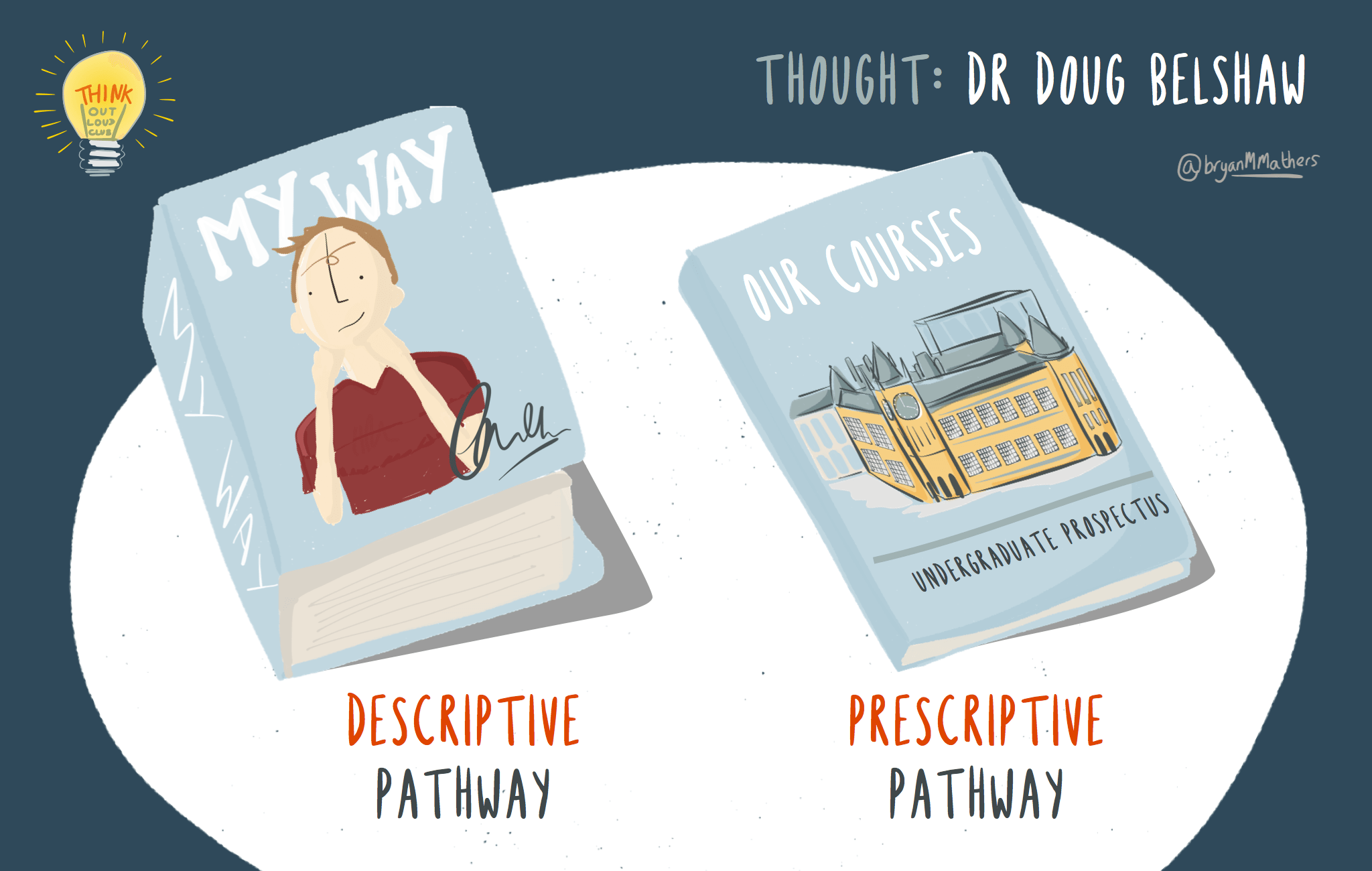

1.12.1 Your Future is Flexible

Nobody knows what the future holds so your future is flexible. This means you can choose your own three personal P’s : Pace, Place and Pathway: (George and Pettifer 2022)

- PACE: By giving you greater control over how much, at what level, and what kind of intensity you study, I encourage you to set your own pace. Take as much or as little as you want, see section 0.4.2

- PLACE: By offering you a greater choice over the physical and virtual spaces in which you learn - remote, on campus, online, hybrid, blended and transnational.

- PATHWAY: By choosing your own path through this course, you can Go Your Own Way. (Buckingham 1977) Collect evidence of the parts you care about with stackable microcredentials while you loop your own lifelong learning loops, see chapter 24

1.12.2 Your Future is Signposted

Some career resources claim (or imply) that they are the all you will need to solve a particular problem or worse: solve all of your problems! Just buy this book, do this course, watch these videos, listen to this podcast, pass this test and all your problems will go away! Rather than continue this trend, this book signposts some of the most useful resources, see figure 1.11.

Figure 1.11: Wondering which way to go at the traffic sign? I’ve signposted the resources that will help you navigate the start of your professional journey. Which route will you take? Picture of a signpost in the Åland Islands, Finland by Sal via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/3Xop adapted using the Wikipedia app

Scientists call signposting citation, so I’ve signposted and cited sources in this guidebook so that you can :

- Follow them if the destinations are interesting or useful

- Check and verify any facts and claims I make in this book for yourself

While this guidebook cites lots of resources, some of them are more important than others. Each chapter summarises these in a signposts section. You’ll find everything else in the references, chapter 51. University and public libraries may also have physical and electronic copies of some of the books listed here.

I’m not suggesting that you read all these books right now, but that if a particular chapter has piqued your interest, these signposts are good places to keep going, if you haven’t already read them. I hope you’ll find these signposts handy for navigating the mountains of advice. Not all who wander are lost. 🗺️🧭

1.12.3 Your Future is Guided

This guidebook to your future accompanies a course that has been co-designed by students for students, with input from academics and employers. It unites several disparate themes into one coherent story, from fundamental questions about identity and wellbeing through to more applied and practical advice on job hunting, career progression and life after University. Resources that do this are typically scattered around in many different places. There is usually no narrative to tie them all together to help students navigate the mountains of advice as they embark on the first stages of their careers. I’ll guide you through the narrative, but it is a flexible descriptive story rather than an inflexible prescriptive one, see figure 1.12.

Figure 1.12: Many formal education courses follow an inflexible prescriptive pathway (right), they lead you through a story from start to finish. This is the way of the University: “our courses” - our prospectus. This course is different, it follows a more flexible descriptive pathway (left) which means you pick your own way through the story. I’ll guide you through the story but you’ll need to choose your way: “my way”. You stood tall and faced it all. You did it your waaaaaaaaaaay. (Sinatra 1969) Prescriptive vs. descriptive pathways sketch by Visual Thinkery is licensed under CC-BY-ND

Although this is a course guidebook used in undergraduate teaching, you don’t need to be enrolled on the course to benefit from reading it, watching the videos and doing the exercises and coding challenges.

1.12.4 Your Future is Constantly Updated

You are reading the alpha version, the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) of this guidebook, last updated on 15 December, 2025. That’s software engineer talk for saying it isn’t finished yet. Subsequent versions, will be continuously and iteratively released on a daily and weekly basis. They will include:

- More quizzes for better interactivity

- More videos on the Coding your Future YouTube channel youtube.com/@coding-your-future, some of which are already embedded here

- Audio interviews with Students in the Coding your Future podcast in chapter 28

- More illustrations throughout the book

- Improved content, finish incomplete chapters

- Fix bugs and typos

- Your suggestions for improvements and corrections, via github etc see section 0.8

I’m taking a release early, release often (Raymond 1999) approach to publishing this guidebook, you could call it agile book development or continuous book delivery, see figure 1.13 (Schuh 2004)

Figure 1.13: Agile software developers make it up as they go along, whereas waterfalling software developers make it all up at the beginning and then live with the consequences. Quote via Paul Downey, thanks psd. It’s the same with natural language engineering (books). I’m making it up as I go along, using agile book development methods. Women who code image by Justice Okai Allotey via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/3Xnk adapted using the Wikipedia app

1.12.5 Your Future is Personal, Emotional and Sociable

A lot of scientific and technical writing is written in the third person or passive voice. It can be cold and impersonal which is fine for academic writing, but can alienate readers. I have opted to use first person narrative where possible as it is shorter, and hopefully more engaging for you to read. Where relevant, I’ve told people’s stories, to illustrate key social points. There’s plenty of emotion here too, because job searching can be an emotional rollercoaster: from anxiety, joy, depression, frustration, hope, anger and englightenment - it’s all here. Learning is a highly emotional process, especially at University where you may also be living away from friends and family for the first time. (Quinlan 2016)

1.12.6 Your Future has no Paywall or Login

You don’t need to pay anything to read this book online because its not hiding behind a paywall, see the license in section 0.12.1. Publishing this guidebook online makes it findable and accessible, something that isn’t true of knowledge locked up inside other books. Your future is openly accessible, see figure 1.14.

Figure 1.14: Your future has no paywall or login. You do not need to pay, enrol, register or remember your username and password because the content of this book is openly accessible. Unlocked padlock image by Simpleicon on Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/6Df3 adapted using the Wikipedia app.

Because this guidebook is openly available online, it is searchable, browsable and linkable too. Everything important has a link, aka a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) including all chapters, sections, subsections, figures, citations and tables.

There are no usernames or passwords because your future has no login. You don’t need to pay, enrol or register for this course. You don’t have to use some badly-designed monolithic learning management system (LMS) bloatware, over-engineered MOOC or annoying enterprise software. Phew! (Hull 2014)

All your future needs is a web browser. Search and browse this material whenever and however you like, on a mobile, tablet, desktop - it doesn’t matter. Your future is openly accessible.

1.12.7 Your Future is Audible and Watchable

This book is not just words and pictures, but includes audio and video as well, for example:

- videos produced by third parties that are used to illustrate key points

- audio produced by third parties that illustrates key points, both individual episodes and whole series

- short videos produced by me, which augment the written content of this book, see the Coding your Future YouTube channel

- the Coding Your Future podcast (Hearing Your Future) which interviews undergraduate students, see figure 1.15 and chapter 28

Figure 1.15: Your future is audible, listen to Hearing Your Future, the Coding Your Future podcast wherever you get your podcasts, see chapter 28. Hearing sketch by Visual Thinkery is licensed under CC-BY-ND

1.13 Engaging With Your Future

I’ve tried to make the content of this book as engaging as possible by including pictures and conversations. Your future is deliberately playful and light-hearted. If you think this guidebook can be improved, let me know via the mechanisms described in section 0.8. I always welcome constructive feedback, especially when it comes via a pull request. Engage, see figure 1.16.

Figure 1.16: This is Captain Jean-Luc Picard of the Starship Enterprise. Engage! (Roddenberry 1966) Fair use image of actor Patrick Stewart performing in Star Trek adapted using the Wikipedia app. Make it so.

1.14 Signposting Your Future

Each chapter in this book has a signposts section, highlighting key reading, watching or listening you could do next. This chapter has addressed the question of why should you bother coding your future? The answer is that your future is your responsibility and no-one elses. There are lots of people can help shape your future, but none more than yourself. Software engineer Robert C. Martin argues this point in his book The Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers. (Martin 2011)

What’s good about The Clean Coder is that it is short (only 200 pages), well written and to the point. The main part of the book covers professional issues in software engineering, some of which I discuss further in chapter 23, starting your future.

1.15 Summarising Your Future

If all that was too long, didn’t read (TL;DR) for you, then you’ll be relieved to hear that each chapter has a TL;DR (executive) summary.

Figure 1.17: There’s always more stuff you should be reading. If this guidebook is a bit Too Long, Didn’t Read (TL;DR) then each chapter has a brief summary at the end. Public domain picture of ancient greek muse reading a scroll (that’s probably too long) via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/3Xoh adapted using the Wikipedia app 🇬🇷

Your future is bright, your future needs rebooting. Rebooting your future will help you design your future. Designing your future will help you to start coding your future.

The TL;DR for this chapter is, you should read this guidebook because it is different to all the other guidebooks. It will help you take responsibility for maximising your future. No-one else is going to do this for you. Your degree will help open up future options, but it is not enough by itself so you’ll need to maximise the return on your investment. Don’t procrastinate because it’s too late when you graduate and YES this will be on the exam (set by future employers). This guidebook has signposts to help you navigate, design, build, test, debug and code your future in computing.

It looks like the reboot has finished, so we’re ready to go. Welcome to your future. In the next part, you will reflect on who you are and what your story is in chapter 2: Exploring your Future.

What’s Your Story, Coding Glory?